Intro to Shareholders’ Agreements

Today we will uncover the details of the mother of all agreements within a startup’s financing structure: the shareholders’ agreement.

Why should you care early about the shareholders’ agreement? We can almost guarantee, the shareholders’ agreement will be consulted by the involved parties earlier than you would think and there are many factors that can influence your founders, investors and even employees. Some things you can’t even control. Unfortunately, many startups fail due to economic reasons and we don’t want to lose additional startups due to internal legal issues.

So, what is it and what does it do? The shareholders’ agreement lays out the rules for every involved investor and, of course, existing shareholders of your company. A shareholders’ agreement done properly will save you from troubles in the future.

Here’s an example:

One of your investors has an affair. He gets caught, gets divorced, and now the investor’s ex-partner owns 50% of those investor’s shares and wants to sell them. Uhoh! Well, if you don’t have a rule set in place to re-purchase these shares, you will get involved in endless emotionally driven discussions that have the potential to paralyze or even kill your startup.

You have more important things to invest your time into! This article will cover the key elements of shareholders’ agreements, various factors and terms to consider tied to them. Remember to get in touch with us directly if you have any further questions!

Once you negotiate terms with investors, we highly recommend consulting a professional lawyer who has extensive startup experience. Their background is important because some terms are special to startups and these lawyers have probably already seen what can go wrong in life.

Here is a list of professionals (we do not take responsibility for the quality of these lawyers).

Accession

This term makes sure that all shareholders join the same shareholders’ agreement and gives security to the current investors that future investors also have to join the same agreement. It is also important to ensure that all shareholders are, remain, or become parties to the shareholders’ agreement.

Right of First Refusal

This term refers to the fact that should a shareholder who wishes to sell all or part of his shares, other stakeholders (i.e. the company and/or the other shareholders) are given the right to buy available shares first for the offered conditions.

Shareholders cannot sell their shares to a third party before having asked current co-investors and/or existing shareholders.

Makes sense, right? Nobody involved wants a random third party investor to join the club.

Here are a couple of key terms:

- Exercise of Right of First Refusal: This describes the process and timeline a sale of shares has to happen. Shareholders need to follow the defined rules.

- Pro Rata Allocation of Right of First Refusal: There is usually a pro-rata rights allocation. As an example: if one investor has 1000 shares he wants to sell and there is one investor “A” currently holding 300 shares and another one “B” has 700 shares and both want to buy the available 1000 shares, then “A” may only purchase 300 and “B” will buy the other 700. If “B” declines the offer, then “A” can buy the full 1000 available shares.

Tag-Along (Co-Sale Right)

A tag-along (also known as a co-sale right) is a right that protects all shareholders if a part or the whole company can be sold. In other words, it´s a common minority right.

Minority shareholders will not sit at the negotiation table and therefore have little influence. The majority shareholders will negotiate the best possible terms. Therefore, the tag-along clause secures that the minorities get the opportunity to sell their shares at the exact same conditions as the majority shareholders.

Purchase Option

Similar to the “right of first refusal”, the purchase option clause defines that shareholders are allowed to buy shares from other shareholders upon the occurrence of certain triggering events.

The difference between “purchase option” and “right of first refusal” are the circumstances and conditions. The right of first refusal comes in when somebody actively wants to sell their stake. The purchase option is applied when specific events occur (for example, a founder dies or leaves the company or an investor becomes insolvent and has to sell his shares).

Drag-Along (So-Sale Obligation)

This is really important! If a predefined majority of shareholders wants to sell the company, then the other shareholders are obligated to sell their shares as well, at the same terms, even if they don’t like it. Hence the name, “drag-along”, also known as “co-sale obligation”.

This a vital clause in order to be able to sell a company as conflict-free as possible. Selling a company or part of it can get very emotional as serious money and consequences are usually involved. When things get to this level, you cannot expect that shareholders make rational or friendly decisions.

Setting the appropriate majority threshold is a bit of a numbers game. As founders, you might want to ensure that you cannot be dragged along if you do not support the deal. However, investors might want to be able to pull the drag-along if a certain number of investors consent to that, or at least to be able to prevent a sale.

In any case, make sure to carefully evaluate the different shareholdings. At the end of the day, the threshold needs to be negotiated.

Confidentiality

This is a common clause in any business. It ensures that investors are not allowed to distribute confidential information about your company. Of course, every investor should agree not to leak confidential information so this clause is a bit of a given.

Non-Competition

The non-competition or non-solicitation clause protects investors and founders against competing with the company and forbids the employment of personnel from the company. Professional investors such as funds often refuse to be bound by a non-compete due to their widespread activities. We suggest to carefully consider the benefits of a non-compete clause for your company.

Cost and Expenses

This is pretty straightforward: usually, each party has to bear their own costs for their lawyers and general fees.

Vesting

Vesting usually applies to founders and employees who are granted any kind of share participation and defines how many shares the relevant founder or employee economically owns at any given time.

It is normal that founders have to subject their shares to a (reverse-)vesting. This protects each founder and each shareholder involved. Here is why:

Let’s say we have two founders each owning a stake of 50%. An investor invests money now. Tomorrow one founder quits and leaves the company.

If there was no purchase option (see above), then a 50% or whatever is left after the dilution, the shareholder would leave the company without further contributing to the development. No investor wants this, as all the results of the efforts put in would go 50% to a party which does not help to make the business a success anymore, so there must be a possibility to repurchase all these shares.

Now, what if the relevant founder left after one year? The founder would have contributed one year to the development. Would it still be fair if the company and/or the other shareholders were able to repurchase all the leaving founder’s shares? If not, how many shares should the leaving founder be entitled to keep? Would that change if a founder left after two years? This is where the vesting comes in.

You should agree to these terms with your co-founder well in advance before you even incorporate your company. Once investors come in, they will look at this term. If it’s not there yet, they will likely ask for a vesting.

How Vesting Works in Practice

Usually, you have a cliff and a vesting period.

Let’s assume you define a linear monthly vesting over four years with a cliff at 12 months.

This means that over the first two months, no shares vest at all, but at the expiration of the 12th month, one-fourth of all shares (i.e. the ones attributable to the first 12 months) vest in one go.

Thereafter, one-thirty-sixth of the remaining shares vest on a monthly basis.

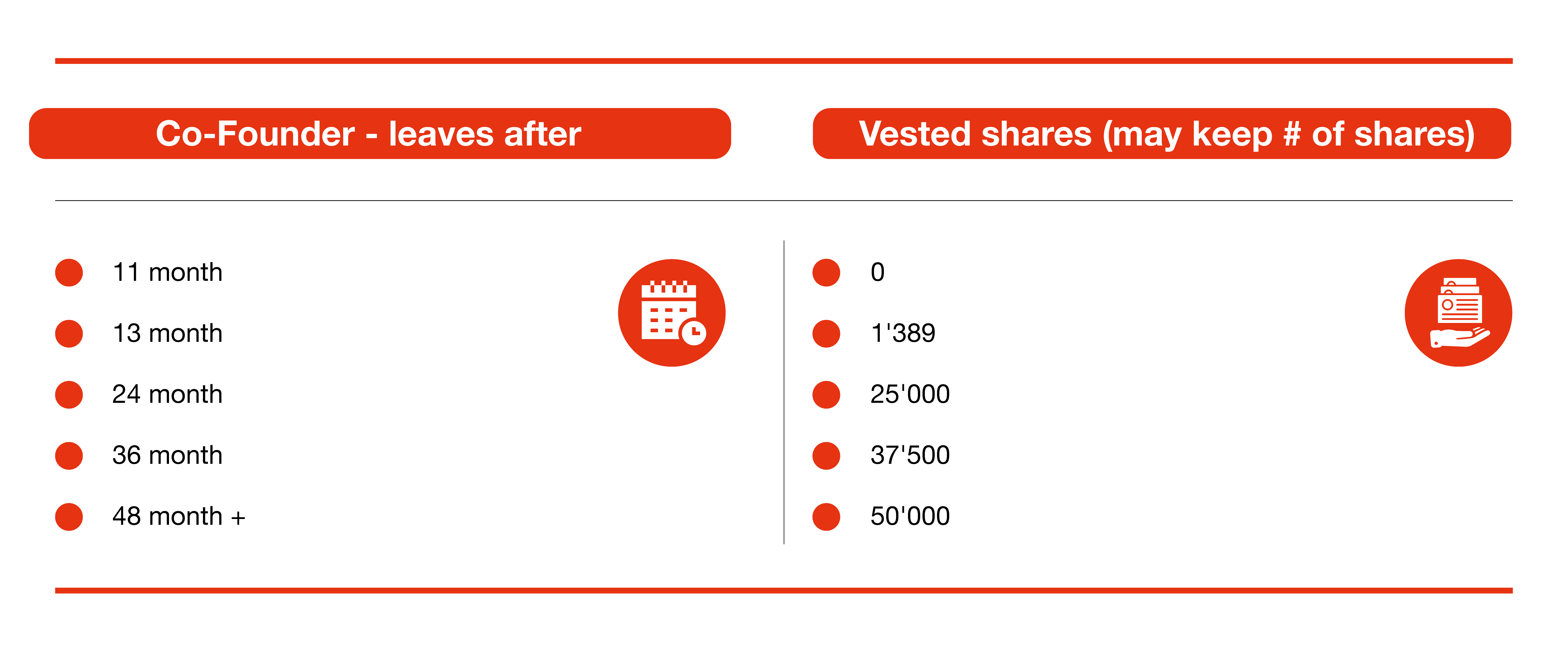

Suppose a founder has subscribed for 50’000 shares. Then the scenarios below apply:

In case the individual under vesting terms leaves before the end of the vesting period, they must sell the shares according to the specific terms to the other investors. This is where the purchase option clause describes the procedure.

Usually, it is the case that the individual who leaves early and has to sell the shares sells them either at nominal value (in which case the person just gets the money back) or at a higher value. This depends on the reason for termination and the structure of the vesting. Other terms can also be defined such as selling at the present or fair market value.

The problem with defining a sale price at present or fair market value is its determination. Is it the value per share of the last financing round? Is it the formula value agreed with tax authorities? Besides that, it could be that nobody involved has the cash to pay that price, which means the shares stay with the person who leaves. In many cases, this leads to the fact that it jeopardizes the ability to raise funds in follow-up rounds, as the company structure is now far from ideal.

Cliff means the period in which no shares at all vest/can be kept until the end of the cliff period is reached. These terms make sure that the executing management stays committed and has skin in the game. Conditions may vary in special circumstances or later-stage startups.

AUTHOR

Julian Stylianou

CONTRIBUTERS

Michael Baier

Ioana Voicu

Michael Moisiman

Adele Bottoni